Paradis Found

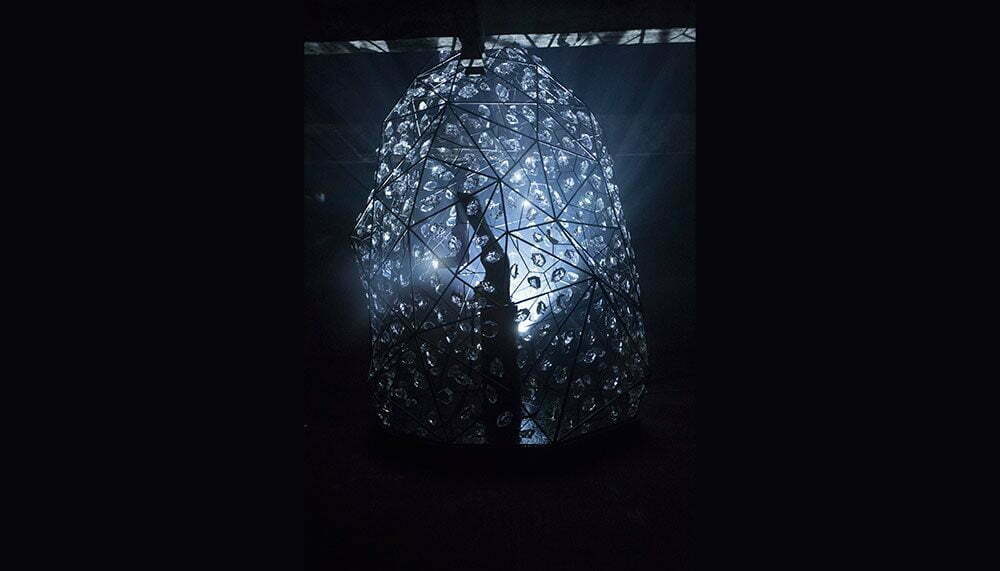

It’s dark. Only a dim glow illuminates the motes floating in the air, making me acutely aware of the damp, subterranean chill on my skin, the ancient, musty note in the air, and above all, the pervading silence. Suddenly, the gloom is pierced by a ray of light projected from an electronic arm that slowly swivels and pivots within a large cage of wire and sparkling crystals. Disconcertingly human in its movements, it swings in a wild frenzy one moment and pauses thoughtfully the next, directing its blinding gaze at one crystal shard, then another.

Titled Quest, this unusual artwork is by London-based design studio Marshmallow Laser Feast. Its setting is Hennessy’s Founder’s Cellar in Cognac, where we’ve been invited to partake in a sumptuous dinner imagined by Michelin-starred chef Guy Martin in celebration of the artwork, the first of its kind to be installed in the space.

Quest reflects the exacting precision and human ingenuity involved in the art of Hennessy’s master blender, who sieves through thousands of eaux de vie to select only the finest to blend a cognac. It’s particularly fitting that Quest’s new home is the Founder’s Cellar – also known as a Paradis – a small, rarefied space in Hennessy’s headquarters where only the oldest and most priceless of the maison’s eau de vie may gain entry. This is no small feat considering that over its 250 years of history, Hennessy has amassed the world’s largest stock of it: over 360,000 barrels, to be exact. Out of these, the finest eau de vie – some of which date as far back as 1800 – are cloistered in the Founder’s Cellar in either oak casks or wicker-encased glass demijohns.

The epitome of this selection process is undoubtedly Hennessy’s Paradis Imperial. Just 10 out of 10,000 eau de vie get the chance to become part of this exalted liquid, the selection of which depends entirely on the intuition and palate of the maison’s master blender.

The man now tasked with this monumental responsibility is 39-year-old Renaud Fillioux de Gironde, who took over the reins in July from his uncle, the seventh master blender Yann Fillioux, creator of Paradis Imperial. Renaud started training for his appointment 15 years ago, learning, among other things, all the references for tasting. “When I became Hennessy master blender," he says, “I was well prepared."

The coveted Paradis ImperialTonight, Renaud is guiding us through a tasting of Hennessy’s Paradis Imperial, a legacy of his forebears that traces its origins to before he was even born. He raises a glittering crystal glass filled with the amber liquid to his nose, remarking on its delicate floral, slightly jasmine character.

“Put a little in your mouth and let all the character through your palate," he instructs, “and you discover that maturity but balanced with the right elegance – that’s the Paradis Imperial experience. It’s quality, it’s precision pushed to the limit."

To gain an insight into just how eau de vie makes its journey from grape to glass, we tour Hennessy’s substantial facility in Cognac, traversing its sun-dappled vineyards, distillery and barrel repair facility. The latter is defined by its dramatic sounds – the hissing of coals used to roast a new barrel, the thunderous whack of iron hammers on old barrels bound with chestnut strips held together by wicker, the skeins of which a strapping cooper tears out with his teeth. Each of their tools is handmade by the craftsmen, with each bevel and handle built to suit their particular grip.

In a landscape dotted with cognac houses, only Hennessy can lay claim to such a facility, which underlines its commitment to precision and control.

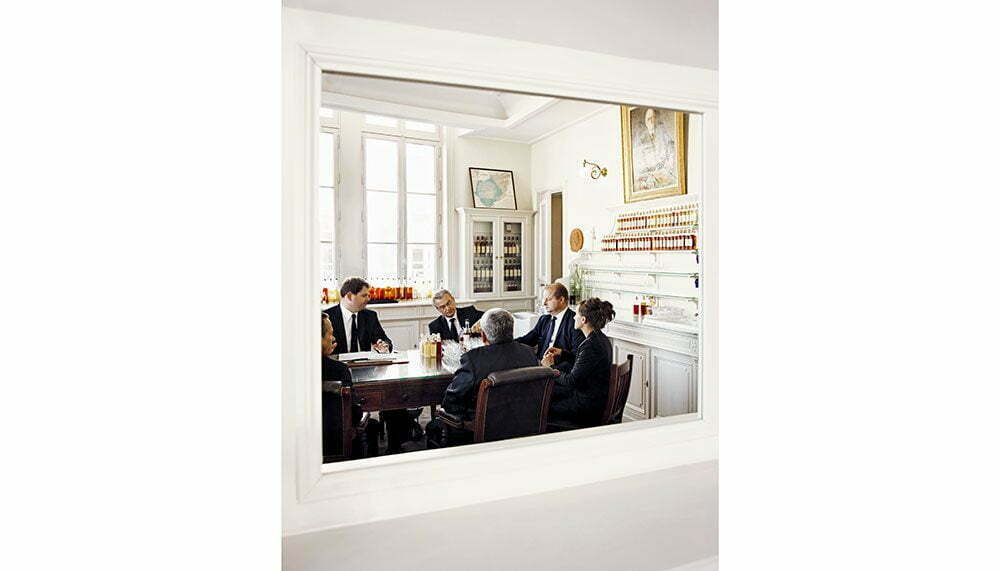

Nowhere is this obsession most evident, however, than in the sacred Tasting Room. It’s a sun-lit, white-walled chamber at Hennessy’s headquarters along the fabled Charente River. The austere space, which contains wall-to-wall shelves housing tens of thousands of phials of eau de vie, is where Hennessy’s Comite de Degustation, or crack team of eight master tasters, led by Renaud, meet without fail every weekday at 11am sharp. “It’s the end of the morning, you’re not tired yet, your body is getting a bit thirsty, a bit hungry, and all your taste buds are just opening and they’re ready," says Renaud, of the magic hour. “This is the moment when your ability to taste is at its best."

Renaud tastes upwards of 50 eau de vie in each session, carefully recording taste references and notes in a dedicated notebook, or grand cahier. Anything that needs to be tasted is brought from the cellars to the tasting room, so that tasters are not affected by variables such as temperature, environment or the people they’re with.

This drive to maintain standards is archetypal of Hennessy, where preserving the savoir faire of the maison is of such importance that master blenders seek recognition for their ability to adhere to the house’s codes during their tenure. “The question is not so much what you want to change or do differently," says Renaud. “The first thing is to maintain the consistency of Hennessy cognac – this is a major priority."

This doesn’t mean a lack of innovation. Renaud has invested considerable time and cost in research and development, as well as gaining an intimate understanding of every step of the production process. He spent seven years working side-by-side with Hennessy’s grape growers, to “ensure what we get every year is even better than the last".

And despite Hennessy’s long, illustrious history, Renaud still sees plenty of room for improvement. He continues to finesse and experiment with the optimal temperature range to age eau de vie or processes as fundamental as how best to press grapes after a harvest.

While he may harness the latest technologies such as big data analysis in improving Hennessy’s product, the time-honoured concept of legacy is always foremost on Renaud’s mind, just like his uncle before him.

Pointing to a young eau de vie before him, he sees its path through time and, correspondingly, the importance of his work. “It’s young today", he says, “but a future generation may use it in 15, maybe 100 years."