ตลอดเส้นทางสายอาชีพศิลปะอันอุดมสมบูรณ์และสร้างสรรค์ของ Marc Quinn เขาเคยสร้างผลงานหลากหลายรูปแบบ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการหล่อรูปเหมือนตัวเองด้วยเลือดที่แช่แข็ง การเก็บรักษาดอกไม้ด้วยซิลิโคนเหลว และการสร้างสรรค์ผลงานศิลปะ 3 มิติ โดยการนำภาพท้องพระอาทิตย์ยามเย็นอันงดงามจากโปสการ์ด มาปิดทับด้วยเศษซากจากเมืองต่างๆ และติดตั้งไว้บนแผ่นอลูมิเนียมที่ยับยู่ยี่ แนวคิดหลักในผลงานของเขานั้นสะท้อนถึงการพึ่งพาสิ่งแวดล้อมอย่างไม่อาจหลักเลี่ยงได้ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นธรรมชาติหรือสิ่งที่เราสร้างขึ้นเอง หรืออย่างที่ Quinn กล่าวว่า “มันคือการเป็นมนุษย์คนหนึ่งบนโลกใบนี้”

“รูปปั้นแช่แข็งเหล่านั้นแสดงถึงแนวคิดที่ว่าเราอยู่ได้ภายใต้เงื่อนไขบางอย่างเท่านั้น และถ้าคุณเปลี่ยนเงื่อนไขเหล่านั้น เราก็จะไม่มีอีกต่อไป” Quinn กล่าวผ่านทาง Zoom จากสตูดิโอของเขาในลอนดอน “ศีรษะที่แช่แข็งอยู่นี้คงอยู่ได้เพราะมันอยู่ที่อุณหภูมิ -20 องศาเซลเซียส ถ้าคุณถอดปลั๊ก มันก็จะกลายเป็นแอ่งเลือด ดอกไม้แช่แข็งเหล่านั้น ดูเหมือนสมบูรณ์แบบก็เพราะมันถูกแช่แข็งอยู่ ถ้าคุณถอดปลั๊ก มันก็จะกลายเป็นก้อนเนื้อเละ”

Quinn เริ่มเป็นที่รู้จักเมื่อกว่า 30 ปีที่แล้วในฐานะหนึ่งในศิลปินกลุ่ม Young British Artists ผู้ไม่ยึดติดกรอบเดิม ผลงานของเขาถูกจัดแสดงอย่างกว้างขวางในพิพิธภัณฑ์ หอศิลป์ และงานศิลปะนานาชาติต่างๆ แต่สถานที่จัดแสดงล่าสุดของเขาคือ สวนคิวในกรุงลอนดอน ซึ่งจะเป็นสถานที่จัดแสดงนิทรรศการ “Light Into Life” ตั้งแต่วันที่ 4 พฤษภาคม ถึง 29 กันยายน อาจกล่าวได้ว่าเป็นฉากหลังที่เหมาะสำหรับผลงานของเขา สถานที่แห่งนี้ไม่ใช่ป่าดิบหรือสวนที่ปลูกเพื่อความสวยงามเท่านั้น แต่เป็นสถาบันวิทยาศาสตร์ที่ได้รับการดูแลอย่างพิถีพิถัน

“มันเป็นหนึ่งในสถานที่ที่มีความหลากหลายทางชีวภาพมากที่สุดในโลก” Quinn กล่าวด้วยความทึ่ง เขาบรรยายถึงตัวอย่างพืชแห้งกว่า 14 ล้านชิ้นในหอพืช และพืชที่ปลูกเพื่อการวิจัยรักษาโรคมะเร็ง รวมถึงสิ่งที่น่าสนใจอื่นๆ ความยินดีของเขาแสดงออกอย่างเห็นได้ชัดของเขาเมื่อทราบว่าดอกไม้วิวัฒนาการมาให้มีสีสันสดใสเพราะแมลงสามารถมองเห็นสีได้ – ไม่ใช่ดอกไม้วิวัฒนาการเพื่อแมลงตามที่เคยเข้าใจกัน

นิทรรศการนี้จะประกอบด้วยประติมากรรมกล้วยไม้ ใบปาล์มขนาดใหญ่ 14 ชิ้น และอื่นๆ ซึ่งเกือบทั้งหมดเป็นผลงานใหม่และติดตั้งกลางแจ้ง นอกจากนี้ยังมีห้องจัดแสดงนิทรรศการภายในอาคาร ซึ่งนำเสนอผลงานหลากหลายของ Quinn ที่สื่อถึงความสัมพันธ์ของเรากับธรรมชาติ เช่น ภาพวาดเซลล์ของมนุษย์และพืช (ซึ่งเขาสังเกตผ่านกล้องจุลทรรศน์ของ Kew Gardens) และผลงานสวนอีเดนในปี 2001 ที่ชวนขนลุกเล็กน้อยของเขา ซึ่งเป็นตารางที่มี DNA ของพืช 75 ชนิด ผู้ชายหนึ่งคน และผู้หญิงอีกคนหนึ่ง “บางทีอีก 100 ปีข้างหน้า ใครบางคนอาจจะสร้างสวนอีเดนจริงๆ กับคนจริงๆ สองคนขึ้นมาก็ได้” เขากล่าวด้วยความนึกคิด ซึ่งในกรณีนั้น เขาและอดีตภรรยาอาจมีโอกาสได้อยู่ด้วยกันอีกครั้งในชีวิตนิรันดร์ เพราะ DNA ของพวกเขาอยู่บนแผ่นวุ้น

ดาวเด่นของนิทรรศการน่าจะเป็นรูปปั้นที่ได้รับแรงบันดาลใจจากพืชพรรณกรรม โดยรวมถึงต้นไม้บอนไซสำริดขนาดความสูงประมาณ 16 ฟุต จำนวน 2 ต้น ซึ่งจะจัดแสดงภายในเรือนกระจกสไตล์วิคตอเรียน “บอนไซถูกมนุษย์ควบคุมให้คงอยู่ในขนาดที่เล็ก" Quinn อธิบาย “มันสื่อถึงการควบคุมธรรมชาติของมนุษย์ เป็นภาพจำลองขนาดเล็กของเรื่องนั้น ผมปลดปล่อยพวกมันกลับคืนสู่ขนาดจริงของต้นไม้ที่พวกมันควรจะโต" ต่อด้วยการใช้คำพูดวิจารณ์เสียดสีที่เหมาะสม เขาใส่ใจประติมากรรม “ต้นไม้" เหล่านี้อย่างมาก โดยการหล่อใบไม้ขนาดเล็กแต่ละใบเป็นทองสัมฤทธิ์

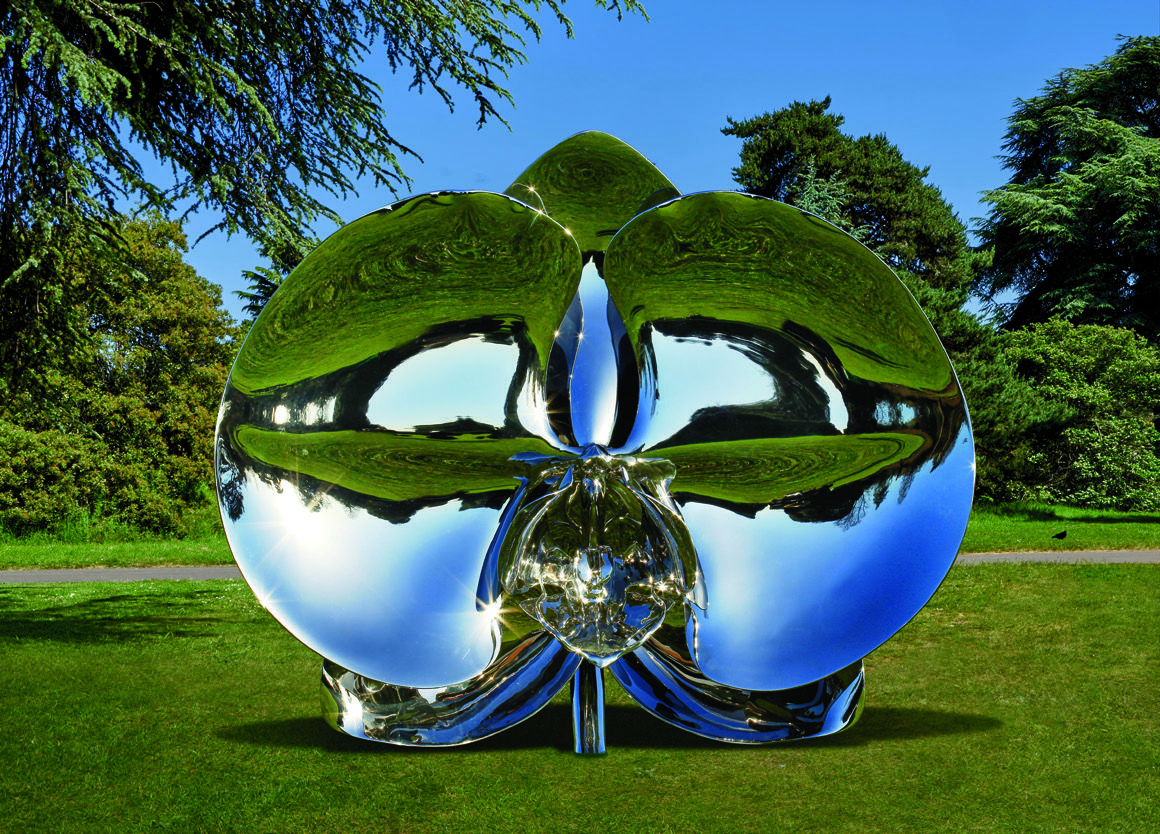

หลายชิ้นในบรรดาประติมากรรมที่จะประดับสวน ล้วนทำจากสแตนเลสขัดเงา สะท้อนทั้งภาพภูมิทัศน์และผู้ชมไว้ในกลีบดอกและใบประดับที่เหมือนกระจกเงา ภาพสะท้อนที่บิดเบี้ยวเหล่านี้จะเปลี่ยนแปลงไปตลอดเวลาตามสภาพอากาศ เวลา และผู้คนที่เดินผ่านไปมา มองจากด้านข้าง ชิ้นงานเหล่านี้มีความกว้างเพียงไม่กี่นิ้ว อาจมองไม่เห็นได้ง่าย “ผมอยากให้มันเป็นเหมือนสิ่งที่มองเห็นได้แต่ไม่เด่นชัด" เขากล่าว แต่เมื่อมองเห็นชัดๆ มันก็คล้ายกับหน้าจอที่อยู่ทั่วไปในชีวิตของเรา ในห้องสีขาว พวกมันคงจะว่างเปล่า แต่ที่คิว พวกมันจะกลับมีชีวิตชีวาด้วยเวลาและสถานที่ “มันแปลกประหลาดและเหมือนหลุดออกมาจาก Alice in Wonderland ในแง่หนึ่ง" เขากล่าวเสริม

การจัดแสดงนิทรรศการครั้งนี้ในสวนสาธารณะแทนที่จะเป็นสถาบันศิลปะนั้น ไม่ใช่เรื่องบังเอิญ Quinn พยายามที่จะก้าวออกจากกรอบสี่เหลี่ยมสีขาวเพื่อให้ผู้คนได้เห็นผลงานของเขามากขึ้น ตัวอย่างเช่น ประติมากรรมหินอ่อนขนาดใหญ่ของศิลปินหญิงตั้งครรภ์ที่ไม่มีแขนชื่อ Alison Lapper (2005) ซึ่งได้รับแรงบันดาลใจจาก Venus de Milo ที่ไร้แขนอันโด่งดังของพิพิธภัณฑ์ Louvre ท้าทายผู้คนที่เดินผ่านไปมาใน Trafalgar Square ให้คิดทบทวนใหม่เกี่ยวกับความพิการและความสวยงาม

“ศิลปะนั้นแท้จริงแล้วเป็นที่สนใจของคนกลุ่มน้อย" เขากล่าว “เมื่อคุณนำเสนอผลงานศิลปะสู่สาธารณะ มันก็กลายเป็นสิ่งที่ทุกคนเข้าถึงได้ ซึ่งน่าสนใจมาก คุณจะได้รับการมีส่วนร่วมและการถกเถียงในระดับที่แตกต่างออกไป บ่อยครั้งที่ผู้คนที่เดินไปตามถนนถูกลดทอนความสามารถ ความคิดที่น่าสนใจบางอย่างก็มาจากคนที่ไม่ได้อยู่ในแวดวงศิลปะ"

จากบทความโดย Julie Belcove

During his prolific and inventive career, Marc Quinn has cast a self-portrait with his own frozen blood, preserved flowers in liquid silicone, and made a series of 3-D works by covering images of postcard-pretty sunsets with urban detritus and mounting them on violently crumpled aluminum. The through line? Our inextricable dependence on our environment, both natural and of our own making. Or, as Quinn puts it, “what it is to be a person in the world."

“Those frozen sculptures bring out the idea that we only exist in certain conditions—and if you change those conditions, then we cease to exist," Quinn says over Zoom from his London studio. “The frozen head only exists because it’s minus-20 Celsius. If you unplug it, it turns to a pool of blood. The frozen flowers, they only seem to be perfect because they’re frozen. If you unplug them, they turn to mush."

Quinn first rose to prominence more than 30 years ago as part of the boundary-pushing Young British Artists and has exhibited widely in museums, galleries, and biennials. But his latest venue, London’s Kew Gardens—where Light Into Life will run from May 4 through September 29—offers what may be the ideal backdrop for his oeuvre: It’s neither wild nor a garden planted with purely aesthetic goals, but rather a carefully cultivated scientific institute.

“It’s one of the most biodiverse places in the world," Quinn says, describing with awe the herbarium’s 14 million dried specimens and the species grown for cancer-treatment research, among other intriguing finds. His delight in learning there, for example, that flowers evolved to bloom in brilliant hues because insects had color vision—and not the other way around—is palpable.

The show will include 14 large-scale sculptures of orchids, palm leaves, and more—almost all of them new and installed outdoors—as well as an indoor gallery featuring a range of Quinn’s works that contemplate our links to nature, such as paintings of human and plant cells (which he viewed through Kew’s microscopes) and his somewhat eerie 2001 take on the Garden of Eden: a grid containing the DNA of 75 plants, a man, and a woman. “Maybe in 100 years’ time, someone will actually make the real garden with two real people in it," he muses. In which case, he and his former wife might have another shot at eternity; it’s their DNA on the agar-jelly plates.

The showstoppers will likely be the vegetation-inspired sculptures, including two roughly 16-foot-tall bronzes of bonsai-style trees to be installed in a Victorian-era greenhouse. “The bonsai has been kept small by humans," Quinn explains. “It’s all about human control of nature—it’s a microcosm of that. I’ve liberated them back to the size of the actual tree that they would have grown to." But in a fitting exercise in irony, he has lavished the same degree of attention on his “trees," casting each tiny leaf in bronze.

Several of the sculptures that will dot the grounds are made of polished stainless steel, capturing both the landscape and the viewer in their mirrorlike petals and fronds. Those distorted reflections will change perpetually with the weather, the hour, and the intermittent visitors. From the side, the pieces are just inches wide and potentially easy to miss—“I want them to be like these visible invisible things," he says—but confronted head-on, they’re similar to the screens now ubiquitous in our lives. If they were alone in a white room, Quinn says, they’d be blank, but at Kew, time and location will bring them to life. “They’re very trippy and Alice in Wonderland in a way," he adds.

That this event will occur in a public garden rather than an art institution is no coincidence: Quinn has long sought to break out of the white cube to reach a wider audience. Alison Lapper Pregnant (2005), for example—a monumental marble of an artist who, like the Louvre’s famed Venus de Milo, has no arms—challenged passersby in Trafalgar Square to reconsider disability and beauty.

“Art is really a minority interest," he says. “Once you put things in the public realm, it becomes for everyone, which is really interesting. You get a whole different level of engagement and debate. Often, the people who walk down the street are underestimated. Some of the most interesting ideas come from people who aren’t in the art world."

From the article by Julie Belcove