Scattered off the west shore of the Malay Peninsula, Myanmar’s Mergui Archipelago is a world away from the tourist-baiting Andaman Thailand is used to. Over 800 limestone and granite islets make up the archipelago, their thick vegetation brimming with wildlife. Slivers of virgin white sand and tangled mangroves hug their shores, beyond which lie colourful coral reefs.

Perhaps the reason for Mergui’s unspoilt nature lies in its relative inaccessibility. A rumbling flotilla of wooden long-tail boats crowds the Thai border at Ranong, waiting to ferry visitors past rows of stilt houses to Myanmar’s mainland Kawthaung. From there, the 80km speed boat journey to Awei Pila resort can take upwards of two hours.

As the mainland melts into the horizon, taking my phone signal with it, I’m left to daydream of the dolphins rumoured to have tailed the boat just a week earlier. A gush of salty seawater to the face is my rude awakening, a result of the day’s rough conditions. I laugh along with my fellow passengers – affluent yet adventurous types, who, I discover, have travelled the world and are seeking destinations unknown.

Aside from the somewhat intrepid journey, the fact that the 800-island archipelago has only been open to foreign visitors since the late 1990s may explain why it welcomes just 4,000 visitors per year and is home to just a handful of resorts. It is most easily accessible from Ranong Airport in Thailand, though Thai visitors will have to arrive via Myanmar’s Kawthaung Airport in order to retain their visa-free privileges – by land, Thai nationals are required to pre-apply for the same US$50 visa demanded of most other countries.

On arrival at the private Pila Island, I teeter down the floating plastic pontoon towards a 600m stretch of flawless white sand. Just hours later, the entire scene is bathed in a candy pink sunset – a spectacle I watch from the wooden deck fronting my sea-view yurt, complete with air conditioning, en suite and al fresco shower. Tired from the journey, I snuggle up in my four-poster bed, draped with ornamental white mosquito nets, as the sound of the nearby waves lulls me to sleep.

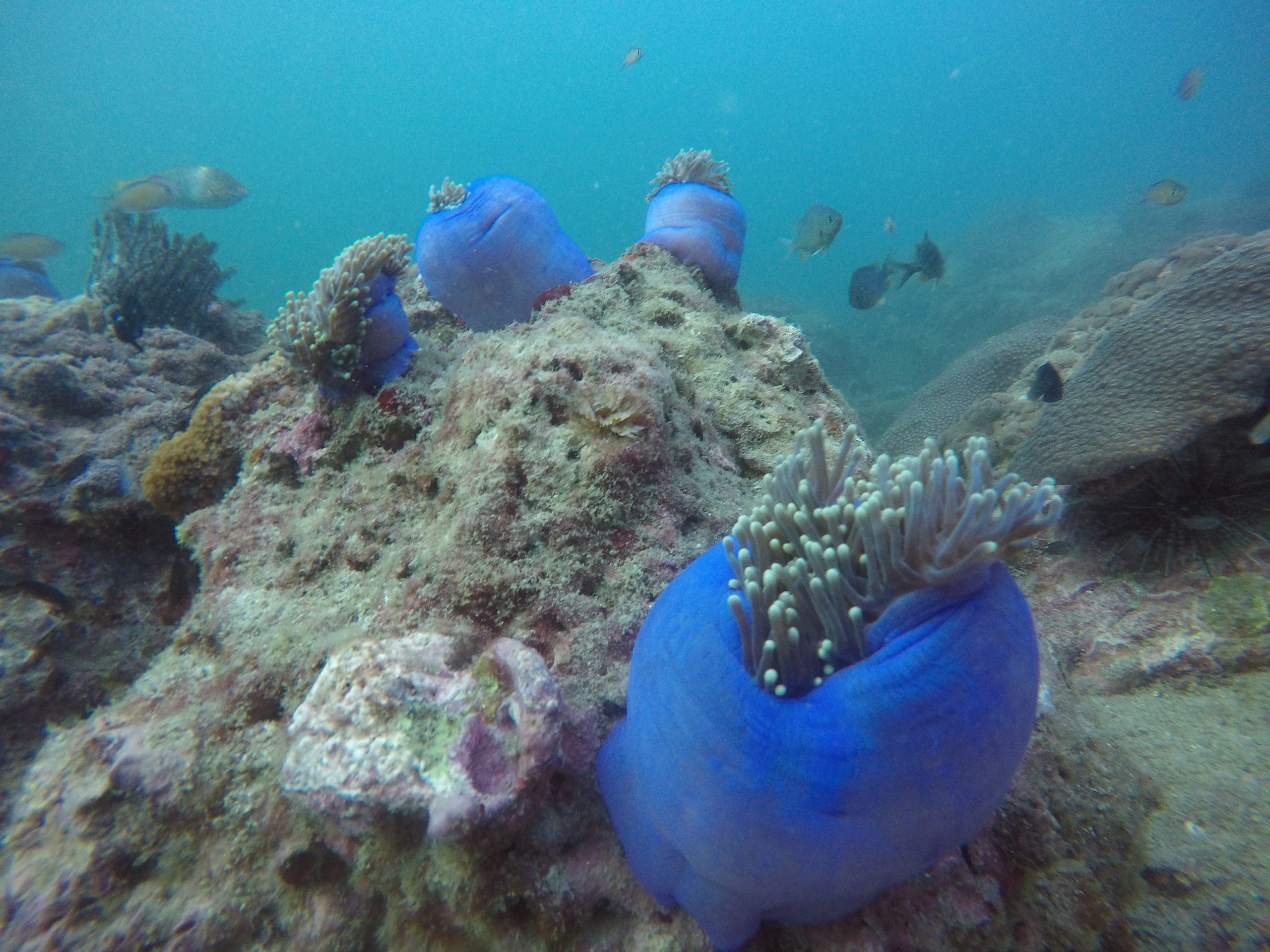

After a gentle yoga and meditation class on the beach, followed by an invigorating bowl of spicy mohinga – a traditional Myanmar soupy breakfast of rice noodles and fish – I’m refreshed and ready to head out to sea with the resort’s experienced scuba instructor, Marcelo Guimaraes. He caters to everyone from first-time divers all the way up to PADI Open Water-qualified experts, who stand the chance of encountering dwarf sperm whales, grey reef sharks and sea turtles. Unfortunately, low visibility clouds our view, though a snorkelling session off neighbouring Long Beach the following day makes up for it with an underwater jungle of coral, clownfish and electric blue neon damsels.

Pila’s marine life is being carefully documented and rejuvenated by Ocean Quest Global, an environmental organisation that has recently embarked on a four-year-long coral propagation project off the island. Led by founder Anuar Abdullah, a small team of divers cultivate underwater coral nurseries, while at the same time monitoring the island’s populations of mouse deer, slow loris, wild pigs, sea otters, plain-pouched hornbills and white-bellied sea eagles. “The land ends up in the water, so if your land’s healthy, it’s going to keep the water healthy," explains team member Jungle Tshongo, adding that they are teaching skills to the locals so they can continue the project after Ocean Quest leaves.

The locals in question inhabit a small fishing village and a neighbouring 40-person Moken settlement, separated from Awei Pila by a 40-minute trek through the forest. Guided by the resort’s recreation manager, Mitch Hawkins, we traverse the dirt path past towering strangler fig trees draped in vines, learning about the island’s edible and medicinal plants as we go.

On arrival at the bay, the sea has drawn back to reveal outcrops of black rock punctuated by moored dugout boats carved from single pieces of wood. These are the traditional fishing vessels of the nomadic Moken, or Sea Gypsy, community, who have roamed stateless through the Andaman for hundreds of years.

It is estimated that the Mergui is home to around 3,000 Moken, around two-thirds of whom have now settled on land, in no small part due to the increased restrictions placed on them by tightened border controls between Myanmar and Thailand.

“I dare say that the Moken have been coming to this bay for hundreds of years because there’s a water supply and it has protection from the wind in the rainy season," says Hawkins, explaining that the villagers are able to remain on the island year-round, whereas the less-protected resort must close from June to September. We observe from afar as women trawl the water’s edge for chitons – edible marine molluscs – and sit chatting outside their palm frond woven huts, their faces tinged yellow-white by traditional thanakha bark paste.

Though the Moken live separately from the neighbouring fishing village, they enjoy a symbiotic relationship, trading their catch with the village chief, who in turn sells it to Awei Pila. The resort’s skilled Italian head chef then puts it to good use in three-course dinners comprising grilled seafood skewers, bouillabaisse stews and tuna tartare.

Just beyond the Moken settlement, ramshackle wooden homes and a small school line the beach, where a small group of children play gleefully on the sand as a tiny puppy scampers by. I brave the steep staircase leading to the village’s modest golden pagoda to take in the panoramic views from the top, before heading back down to enjoy an ice-cold Myanmar beer at the minimart; marked only by decorative stars above the doorway, this humble hut couldn’t be further from the ubiquitous lights of Bangkok’s 7-Elevens. Once we’re suitably refreshed, the resort’s speed boat arrives to sail us away into the red orb of a sunset.