By Chanida Cee Charuchinda– Robb Report Thailand

In the elite world of high jewelry and private collections, only a select few gemstones rise to the rank of timeless icons. Among them, three stand apart—the blue sapphire, the ruby, and the emerald—each from a different mineral family, yet united by their enduring scarcity, cultural significance, and unrepeatable natural origins.

Often referred to in collector circles as “The Three Kings," these stones are not merely beautiful—they are geological miracles, coveted not for passing trends, but for their inherent purity, provenance, and irreplaceable formation. And for the refined collector or discerning investor, the opportunity to own even one in its most natural, untreated form is a pursuit both intellectual and emotional.

Sapphire, Ruby, Emerald: The Trifecta of Prestige

These are not stones for the mainstream market. We speak here of natural-color, untreated, high-clarity specimens with prestigious origins—a class of gemstones that occupies less than 1% of all stones seen in the trade today.

- Blue Sapphire (a variety of corundum, Al₂O₃): The most revered specimens hail from Kashmir, Burma (Mogok), and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The finest stones exhibit not only high saturation, but also a velvety, soft diffusion of light caused by microscopic rutile silk inclusions—best seen in Kashmir sapphires.

- Ruby (also corundum): True pigeon blood red rubies from Mogok remain the holy grail. Their fluorescence under UV light and minimal iron content give them an unmatched inner glow.

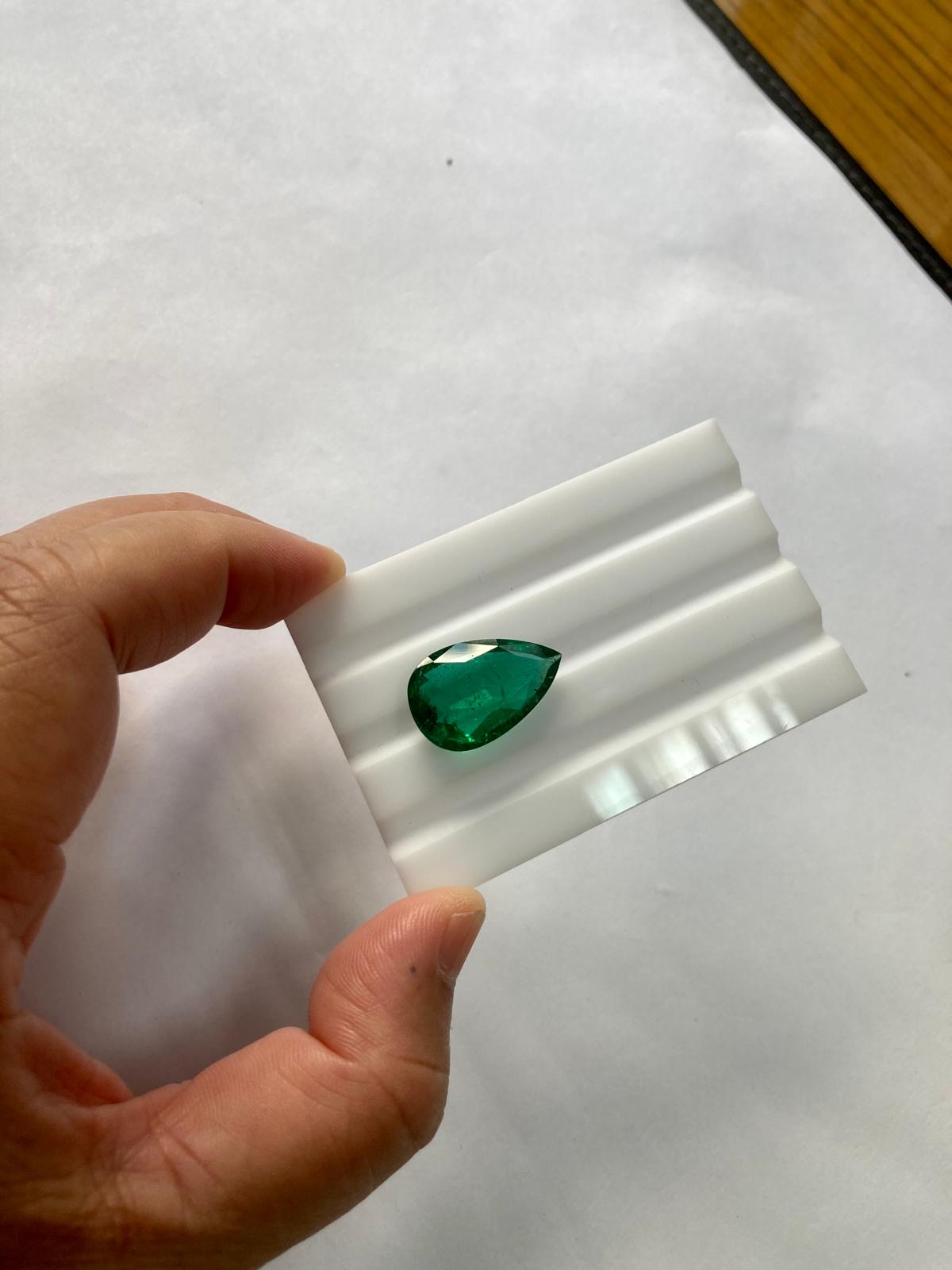

- Emerald (beryl, Be₃Al₂(SiO₃)₆): The most collectible emeralds are from Colombia, specifically the Muzo and Chivor mines. Unlike other gems, emeralds are judged in terms of “jardin" (garden) inclusions—natural fingerprints that do not detract from value but enhance authenticity.

Each belongs to a different geological setting, formed under unique conditions of pressure, heat, and trace elements—factors impossible to recreate. As a result, they are increasingly viewed as finite legacy assets, akin to rare watches or Impressionist masterpieces.

No Heat, No Oil, No Compromise

In today’s gemstone market, 95–98% of sapphires and rubies are heat-treated. Emeralds are routinely oiled with cedar or synthetic resins to improve clarity. These enhancements are accepted practice in commercial jewelry—but in the collector and auction world, they reduce the stone’s rank by several orders.

The true connoisseur demands gemstones with no indication of heat (sapphires/rubies) and minor or no oil (emeralds). These are verifiable through advanced spectroscopic and microscopic testing by prestigious laboratories such as Gübelin, SSEF, GIA, ICA|Gemlab, GIT, and Lotus Gemology. Their certificates serve as passports in the global gem market, validating both rarity and investment potential.

Notably, the finest unheated sapphire or untreated ruby can command 5x–20x the price of its heated counterpart. The price differential is not just about rarity—it’s about integrity of formation and future value preservation.

Origin Determines Everything

Gemstones are the only luxury objects whose value is intrinsically tied to both natural origin and human history. A 3-carat sapphire from Kashmir, a 2.5-carat ruby from Mogok, or a 4-carat emerald from Muzo, all untreated—these are not interchangeable with stones from Madagascar, Mozambique, or Zambia, even if similar in appearance.

Why? Because origin determines the chemical fingerprint, optical performance, and storytelling potential. It adds an aura of mythology and permanence. From the closed mines of Kashmir to the lost shafts of Chivor, these locations are no longer producing at scale—if at all. This alone makes them non-replicable, which is critical for long-term value.

From Earth to Auction: The Provenance of Prestige

The path from mine to market is rarely linear. Stones are extracted from ancient riverbeds and marble fissures by artisanal miners, passed through hands of traders in Yangon, Bogota, or Ratnapura, then cut in Geneva, Jaipur, or Bangkok. Each gem has a provenance trail, and for serious collectors, documentation of this journey increases both liquidity and legacy value.

Auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips now curate high-jewelry sales specifically featuring unheated, origin-certified stones. The rise in demand from global UHNWI buyers—particularly from Asia and the Middle East—has placed consistent upward pressure on top-tier prices.

Consider the 392-carat Blue Belle of Asia, a Ceylon sapphire sold for USD 17.3 million in 2014. Or the Sunrise Ruby, a 25.59-carat unheated Burmese ruby sold for over USD 30 million—both set global records, but more importantly, they redefined gemstone collecting as serious investment-grade territory.

Why Collect Now: The Window Is Closing

Mining yields are dropping. Kashmir is exhausted. Mogok is heavily regulated. Colombian emerald mining is increasingly restricted. Meanwhile, the gem market has become more transparent, certificate-driven, and global.

For collectors who value both aesthetic and asset potential, the “Three Kings" offer a rare alignment: wearable legacy, museum-worthy provenance, and future liquidity. These are not speculative purchases; they are wealth preservation through geological history.

Final Thoughts: The Collector’s Eye

To acquire a no-heat Kashmir sapphire, a pigeon blood Mogok ruby, and a Colombian emerald of top pedigree is to hold not only the three kings of color—but to join an elite lineage of collectors, from royalty to rock stars, who understand that true luxury lies not in the obvious, but in the eternal.

In a world obsessed with speed, technology, and fleeting trends, these stones remain quiet monuments to time, pressure, and purity. And for those who can tell the difference, there is no substitute.